Sun slips through the gaps in protest signs and raised fists, glancing into the lens of Damian Lillard’s phone camera to create a flare and flicker of light in the live video he’s recording of the Portland protest he’s joined. It was the 8th day and night of protests in Portland, a mirror to what’s happening across the country and worldwide, against the murder of George Floyd and the ongoing police brutality across the United States. Lillard’s voice echoes thousands of others in rolling, call and response chants of “Whose Streets? Our Streets”, “Black Lives Matter” and the individual naming of George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery and Breonna Taylor. When the chorus shifts to “No justice, no peace”, while the audio in the recording of Lillard’s video has made his voice sound singular throughout, when he begins to repeat, “No peace, no peace, no peace” there is a pronounced emphasis on both words, a deliberate attention as his breath slows and gathers before each word, over and over — No. Peace. — that resonates.

Lillard has always been a master of control, in his steadiness and gift of foresight on court, his ongoing activism and exacting responses equating the sick to sports narrative with slavery. He is one of the most consistent players and people involved in the NBA and has worked, primarily through his actions, toward the legacy goal of his own words in “being a more solid person than a player”.

In his continued commitment to character, to being sincerely himself, Lillard is, much to the NBA’s luck, almost archetypal. He is an exemplary athlete, his activism and athletic skill are equally balanced, cooperative and endorseable. That’s why, when Lillard was accused recently of being a “spoiled and entitled brat” by ESPN’s Dan Orlovsky for saying he had no desire for the Trail Blazers to return to play in the league’s proposed bubble, he also exemplified the league’s current and blatant disconnect.

As a competitor, Lillard made it clear there was no point for him or his team to return once the season resumed if there was no numerical way for them to have a shot at the playoffs. At that point, like now, there were also no clear plans in place when it came to player safety given the ongoing spike of COVID-19 cases across the U.S., including Florida, where the league will make its return.

Orlovsky’s response centered mainly on a desperate attempt to draw gossamer parallels between what the ravages of the pandemic have taught us — to not take anything for granted, that frontline workers are required to “have to go do things” — and Damian Lillard deciding he was fine with not playing basketball right now. Aside from being grossly reductive to the work being done by those on the frontlines, all who would prefer Orlovsky’s breathless reaching be directed at pressure on, perhaps, government that can increase hazard pay or allocate more resources, it clarified a problematic point still entrenched within pro sports and those who push it, that the spectacle of performance is more essential than the people participating. That basketball, the act of playing it, and the structure it is encased in precedes the very engine, its players.

The NBA announced the ratification of its plan for the season to restart in a bubble league in Orlando in July the same day the state of Florida recorded its greatest increase of COVID-19 cases thus far and while many American cities were smoldering. Despite the ongoing pandemic, Americans have been in the streets for two weeks demanding justice for George Floyd and the barbaric practices of policing Black people. Protests have been unilaterally met by more brutality from the police responding to them, which has increased the volume of protests, a rising cycle of abuse and response that NBA players have joined by lending their voices and platforms or physically showing up to march. Jaylen Brown, Tobias Harris, Malcolm Brogdon, Enes Kanter, Aaron Gordon, Kyle Kuzma, Terry Rozier, Lonzo Ball, Klay Thompson, Stephen Curry, Giannis Antetokounmpo, and Lillard are just some of the players who have been protesting in demonstrations across the country. As a league, the NBA has a long and supportive history of civil unrest, with its players calling for change and reformative action in the face of social injustice. There have been times, however, when the league has been slow, and at times unresponsive, to backing its players in their efforts, especially if they represented a potential disruption to the continuity of the game itself.

When Bill Russell and his Black teammates were refused service in a Lexington, Kentucky restaurant prior to a Celtics preseason game, Russell and his teammates boycotted the game. In 1966, when Russell became the head coach of the Celtics, he faced relentless bigotry and was deemed difficult by white media and unfriendly by white fans who would later break into Russell’s home to damage his trophies, cover the walls in racist graffiti, and defecate in the beds. The FBI held a file on Russell that described him as “an arrogant Negro who won’t sign autographs for white children”. During his tenure, the Celtics offered a survey to fans in hopes of increasing attendance, the over 50% of the response was that there were “too many black players.” He delivered the city back-to-back championships.

Craig Hodges was a pioneer in the NBA’s 3-point game and helped the Bulls to their first two titles with his leading 3-point percentage. As a social activist and Muslim, when the Bulls were invited to the White House, Hodges handed George Bush a letter opposing Desert Storm and raised concerns with racism within the U.S. Shortly after, Hodges was dropped by the team and his 10-year career came to an abrupt end. Four years later, he would go on to file a $40-million lawsuit against the league, claiming the league was embarrassed by his action at the White House. The case was thrown out on a technicality — the statute of limitations on racial discrimination cases was two years.

In the NBA’s current rulebook protests are “not permitted during the course of a game.” The rule book also states that players, coaches and trainers “are to stand and line up in a dignified posture along the sidelines or on the foul line during the playing of the National Anthem.” These rules were already in place when Colin Kaepernick began taking knee in the NFL, and many NBA players wanted to act in solidarity with Kaepernick and his protest against oppression, the overt killing of Black people and police brutality. The league didn’t yield on that rule, and players instead stood with arms locked during the anthem, heads bowed in silence.

These same rules were in place when Nuggets guard, Mahmoud Abdul-Rauf, refused to stand for the anthem in March 1996. Initially, Abdul-Rauf would linger in the locker room, or stretch when the anthem was played, and it was not until he was asked by media about that the gesture — his response to the flag being a symbol of oppression and systematic racism and that standing for the anthem would conflict with his beliefs as a Muslim — became a point of contention. On March 12, 1996, former commissioner David Stern suspended Abdul-Rauf. Days later he agreed to the league’s compromise of standing with his head bowed and eyes closed during the anthem. In response, two Denver DJs trespassed into a mosque and played the American national anthem with their trumpets “as a stunt,” Abdul-Rauf was traded in a career-high season to the Kings where he lost his starting spot and would be out of a career a year later at 29. Five years later, his house in Gulfport, Mississippi, was burned to the ground.

Claiming that these instances were of their time may be historically correct but not any less problematic or prime examples where the league placed the value of the continuity of play above the league’s players, its own people. Russell has somewhat since reconciled with the Celtics but after everything he went through, he had no responsibility to, and Hodges was ostracized anew by the framing he received in The Last Dance. Abdul-Rauf was a player at the height of his career who opted to use his platform and likely hoped it would afford him some measure of protection against retaliation, overt or surreptitious. Instead he received neither.

League-backed instances of activism and protest are often equated to the changing of the guard from Stern to Adam Silver, but many occurred while Stern was acting commissioner. What they have in common is that they, for the most part, happened off the court or, when they overlapped with the game, they were statements that sprung from a backstory and had a reference point needed in order to be understood.

When Phoenix donned their Los Suns jersey on Cinco de Mayo in 2010, it was to celebrate the holiday, but it was also a statement opposing the introduction of the state’s strictest anti-immigration law to date. The law, SB 1070, allowed local police to check the legal status of those they suspected to be undocumented immigrants at random, an action that led to increased and emboldened racial profiling of the Latino community in Phoenix. Fans and locals understood the gesture, but the jerseys, which had been introduced in 2006, did not raise much response of reaction beyond that instance. Similarly, when Trayvon Martin was murdered in February 2012, the roster of the Miami Heat would respond by donning hoodies before a game in late-March in honor of what Martin wore when he was shot in his family’s own neighborhood. It was LeBron James who would tweet the photo the team took together out.

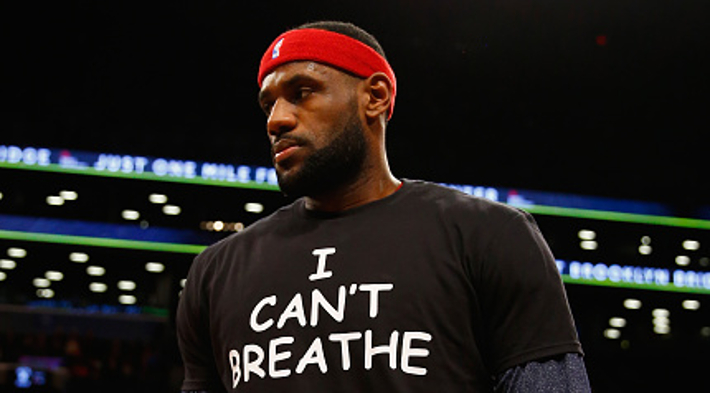

James has become the NBA’s most prominent voice on social justice and inequality, and it has been through the prolific platform he’s cultivated. This initially came through social media, where James currently sits at 112 million followers across Twitter and Instagram, and later through his far-reaching philanthropic efforts and multidimensional media company, UNINTERRUPTED. James is his own network and it is hard to imagine his career being derailed by the act of speaking out. By and large he is looked to by the league itself and its community of players as a barometer of response, a role he has fully and meaningfully inhabited since his and the Cavs “I Can’t Breathe” shirts in response to Eric Garner’s 2014 murder, his turning Fox’s Laura Ingraham’s beautifully backfiring “Shut up and dribble” into a mantra and movement, his calling Trump a “bum”, and now, again, in standing up amid widespread unrest.

It is the platform of its players that the league understands to be the most powerful, and where, at times, it rightly takes backseat and lets players speak for themselves. In the peak of Kaepernick’s protest, Silver and former NBA Players Association Executive Director, Michele Roberts, wrote an open letter to players, encouraging them to speak up on “critical issues that affect our society also impact you directly”. The messaging was by no means hollow, but it was also a step that, intentional or not, diffused the question of whether or not NBA players would kneel during the anthem. As younger and more communication savvy generations are drafted into the league each year, fluent and in some cases better and more quickly informed on social issues as they develop than executives in the league, there will be less of an inclination from them to wait. They’ve grown up in a world where things don’t always get addressed or get better. They want what is actionable, fast and impactful.

Like James, the league’s own efforts in activism, championing progressive causes and social response have been far-reaching and genuine. In its Represent Justice campaign, it has brought teams into American prisons for games and to encourage dialogue and break down stigmas associated with those incarcerated, the majority of whom are disproportionately Black. It works with many non-partisan organizations to host voter registration events and through NBA Voices the league has partnered with community organizations working to address inequality including the Equal Justice Initiative, Athlete Ally, Innocence Project, Rise and many more. Internally, it is a league striving to create better resources for its players, investing in their performance as much as their mental health.

But still, where the league gets snagged is where these efforts don’t align with its business model and sole product — basketball. It was less than a year ago when Rockets GM, Daryl Morey, tweeted his support for Hong Kong protestors and their anti-extradition action. Morey was swiftly brought to heel. In his statement, Rockets owner Tilman Fertitta distanced himself and the team from Morey, and the league’s response called Morey’s statement “regrettable.” Silver lamented the economic impact of the tweet while insisting the league was supporting Morey, admitting that “China” demanded Morey be fired. The fallout grew even stranger, with right-wing U.S. politicians celebrating Morey for standing up to China, many who aligned themselves in policy and action with Trump, who the NBA’s players have spoken out against since he first took office. What was clear was that while Morey exercised a tenant of NBA to speak out and speak freely on critical issues, he did so where it stood to hurt expansion efforts and the league’s bottom line.

The push by the NBA now to resume doesn’t just bulldoze over a pandemic, it bulldozes over hundreds of thousands of voices in anguish, demanding change. It is hard to know what the U.S. is going to look like in two weeks, let alone by the end of July when professional basketball is set to resume. Will protests continue to gain momentum? Will the pandemic?

The NBA is a large, private corporation. It can be easy to forget that because they employ some of the biggest personalities whose outspoken tendencies accelerate our familiarization and resulting fondness to them. That and the sport is so visible. Watching, you begin to get a feel for an individual player’s tics and range, you are tied up in their visceral triumphs. The NBA is also a global leader in progressive action that through its outsized financial gains, meaningful partnerships and independent initiatives, has contributed to some of the most profound change in the way sports are representative of something greater as much as they are played and consumed. What recent months have laid painfully bare, whether or not you watch basketball, is that there is no point to idle in the murk of the middle ground and its helpful obfuscation. To have staying power, people and corporations need to move in a collective direction where words match action.

Sports are the ultimate distraction, and leagues are in the business of making their fans comfortable and happy. It’s why the NFL fought so hard to keep players from following Colin Kaepernick’s lead and kneeling during the anthem, and why the NBA preemptively reminded players of its code of conduct regarding the anthem. However, things like systemic racism and police brutality cannot be ignored or set aside at any time, particularly in a league made up of a Black majority. Money and effort to help activism and the fight for justice off the court is important, but the league knows it has the biggest impact when fans are watching games. Adam Silver recently joined Inside the NBA where he promised that the league would listen and learn. That commitment is the correct tack, but there comes a time when simply being responsive is no longer enough. When millions watch the NBA return in a matter of weeks it will be an unprecedented opportunity for the league to step up and use their greatest platform to further amplify and legitimize — to those who have difficulty reconciling the real world with athletes they already hold in a bubble — the work their players are doing within their communities and the messages they have been shouting alongside thousands in the streets.

There is a growing line of dialogue that says whatever happens this season, and whoever wins the title, it will have been an asterisk season. It will, in effect, not count the same. The NBA’s history of social action is an authentic one, and where it has missed the mark or come a step too late it has most often, where it counts, made up for it. How it chooses to move forward now when that motion seems entirely set will make all the difference on where that asterisk settles, and if it denotes a league identity referred to as before and after with hesitation, or with a pronounced emphasis, a deliberate attention — something that resonates.